Merry Trucking Christmas!

Thousands of truck drivers working on cross-border corridor routes in southern Africa will be spending Christmas on the road and away from their families. They will get no holiday break from the exhausting and poorly-paid work routine which these footsoldiers of global supply chain capitalism are accustomed to. Copper anodes and cobalt concentrate from the mines in southern DRC and the Zambian Copperbelt need to reach ports like Durban and Walvis Bay. From there, back loads of machinery, process chemicals and milling balls must get to the mines. The wheels must keep turning.

What is especially frustrating for many truckers is that they will actually not be moving at all. They will instead be stuck in a cue, possibly for several days, at Wenela (on the Namibia/Zambia border), Kazungula (Botswana/Zambia), Beitbridge (South Africa/Zimbabwe), Chirundu (Zimbabwe/Zambia) or one of the other border crossings across the region. Yet those drivers will consider themselves lucky compared to their colleagues at Kasumbalesa on the DRC/Zambia border. To most drivers, this is the busiest, dirtiest and most dangerous border of them all, and an entry point to a cross-border trucker's hell on earth: the Democratic Republic of Congo. Yet Kasumbaleza with its endless cues, blockades, extortionist thugs (some with and many without uniforms) and explosions has in recent months been challenged as every trucker's least favourite place to be.

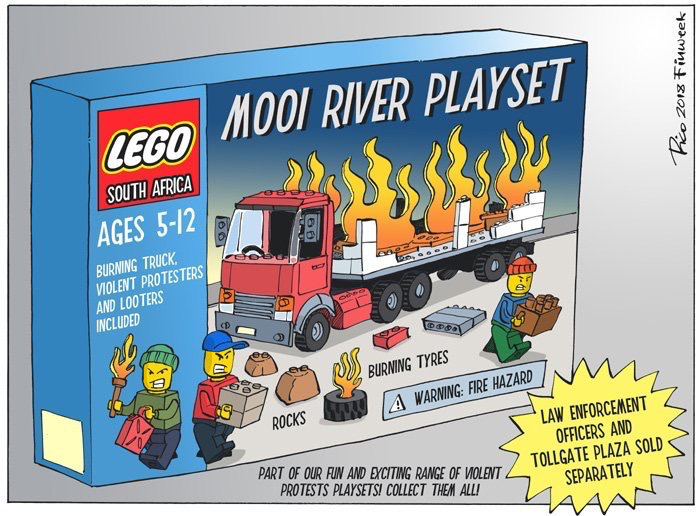

On 29 April 2018 35 trucks were set on fire at the Mooi River Plaza toll gate along South Africa's N3 route to Durban. Already before, and numerous times since this widely reported incident there have been similar such attacks. The South African police has so far made little progress in finding the perpetrators, their ring leaders and motivation for these acts. They appear to be driven by (and deliberately stoking) an explosive mixture of openly expressed xenophobic rage against "foreign" truckers "stealing" jobs from South Africans, aligned with destructive political and economic opportunism. For some of those feeling abandoned by the ANC government's failure to deliver on the post-apartheid promise of wide socioeconomic development, waylaying has become the method of choice. Already common practice in DRC and in Zambia near Kasumbalesa, blocking and looting trucks where terrain, congestion or toll gates and other checkpoints force drivers to shift down has become routine in parts of South Africa as well. For truckers on the Lubumbashi-Durban route, there is now reason to be afraid of what awaits them at both ends of their journey.

Ding! You have 65 new messages.

In Southern Africa, Whattsapp has in recent years become what CB radio used to be: the default mode of electronic communication for truckers, logistics industry managers and transport policy makers.

Over the past 3 years of research for the ARIGOS project on Transport Corridors in Africa I have built up a network of personal contacts in this field, and become an active Whattsapp user myself. Most of the dozens of messages I receive on any given day come via the various groups administered and used by transport industry insiders to communicate with each other. It has been an at times fascinating and tiring, horrifying and hilarious, alienating and endearing experience to read, watch and listen in on the chatter in these channels. Among the most prominent themes are news and sometimes graphic images of the latest accidents, attacks and carnage as well as vignettes of religious wisdom and well-wishing. But the groups are especially active when a specific incident brings truckers' constant frustration to boil over. The violent harassment or even killing of a fellow driver by thugs or security services, a hike in fees and bribes demanded at checkpoints and overnight parking places - images and videos, written accounts and voice messages of such incidents will be instantly shared and re-posted on the various groups. Does this lead to collective action and meaningful change? Yes and no. Occasionally, truckers are organizing to force recognition of their grievances through blockades. One problem with these tactics is that stoppage is often part of the problem for which they wish to see a solution: If you are already standing in a 20km line of trucks waiting to cross the border, how do you draw attention to your grievances by refusing to move?

Formal unionisation in the Southern African trucking industry is weak, and virtually non-existing for cross-border truckers. Drivers nevertheless manage to make their voices heard. Some lower and middle level managers - both corporate and governmental - are members of some of the trucker Whattsapp groups and vice versa. Some of the manager groups are dedicated to problem-solving along specific corridor routes or at SADC level across the region and share the concerns , though typically not the actual experience, of truckers out on the roads. But with a volatile election looming in DRC and a regional economy still largely based on the extraction and overseas export of valuable commodities, the 2018/19 holiday season does not offer much to celebrate for those whose job is to keep the wheels turning.

Dr. Wolfgang Zeller

South African cartoonist Rico Schacherl's take on the April 2018 Mooi River attacks

The author with truckers at Wenela border in June 2018